Wang is a 25 year old construction worker from a small village in the Hubei Province of China. Along with his family and everyone else in his village, Wang was forced to leave the only home he had ever known, because of the construction of the world’s largest hydroelectric power station in the Yangtze River, known as the Three Georges Dam.

Wang is just one of millions of Chinese peasants that migrated from their homes to urban China – in Wang’s case, Beijing. The comfort was a dream, though – more opportunity to future generations, higher salaries and therefore, an improved quality of life. Statistically, this is the case; the average farmer in China has a monthly income of 175 Yuan ($25 US), while an urban Chinese resident receives 580 Yuan ($85 US) , a greater than threefold difference. The World Bank reports that the average rural-urban income ratio in most of the countries is 1 to 1.5.

When one further considers these numbers, one is forced also to think of health related issues, such as the lack of health and unemployment benefits for rural residents. With a population of 1.3 billion and 900 million farmers in impoverish conditions it is no mystery that China is experiencing one of the biggest, fastest, and continuous exodus in human history.

It is true that migrants will have a better income, but do they really have anything to be optimistic about? Have the increased wages actually changed their quality of living? It is difficult to say yes with any degree of certainty when one considers what is newly injected into their lives along with the increased capital; long working hours and increased safety hazards. Hence, a social crisis is rumbling in China, fueled by imbalanced economic growth. It is unlikely that it will achieve the wealth and global success it certainly could, as long as they are not able to find a solution to increase their farmers’ income and spread economic wealth to the majority of their population.

Meanwhile, the international agenda for the Chinese government during the last decade has been to present them as a rich and prospering nation through a lavish display of state-of-the-art architecture produced by a legion of international ‘star architects’ that culminated with the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games. In reality, this is a country with exponential growth in its cities that is leading to rural displacement and all the social and economic problems that ensue. Urban planning, for example, in an area of such rapid growth, is beyond complex with endless pressing problems.

So who is at fault? Where is the blame to be placed, given the level of complexity in such a situation? Clearly, there is no single person or group responsible. Sadly, there has really been no time for thoughtful deliberation and exploration of the kind required; the kind that would have been an integral part of urban development in areas where growth was not at breakneck speed.

In most areas of new urban development, three main types of architecture are readily identifiable. The first one being areas for globalization with factories and urban parks funded by international corporations looking for low-cost labor. The second one is defined by spaces for consumption like shopping malls, hotels, theatres, apartment buildings, and supermarkets for the new Chinese bourgeois class and, finally, the ‘informal cities’ with little or no infrastructure for rural migrants and low income residents.

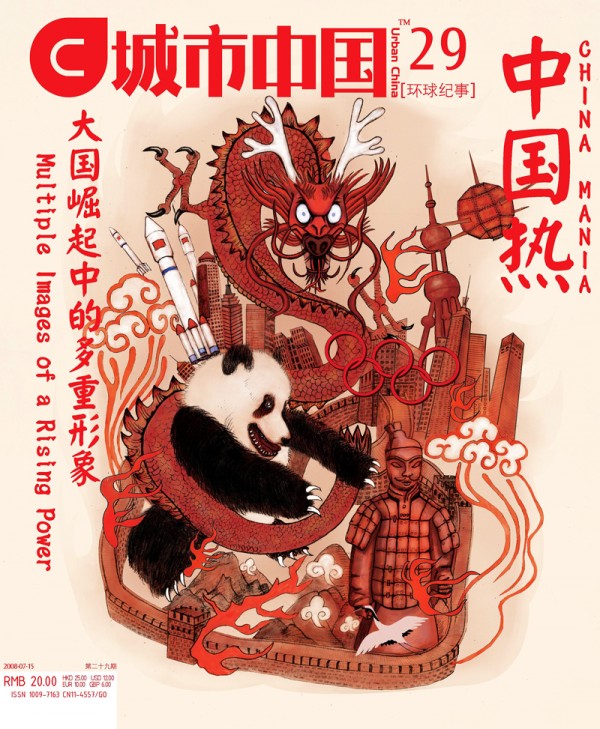

It is within these ‘urban villages’ that their dwellers create innovative solutions for daily-life through the reuse and reconfiguration of objects intended for other applications. A recent exhibition named ‘Urban China: Informal Cities’ opened in February 2009 in the New Museum in New York City, a collaboration between three institutions including the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago and the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, as a showcase for Urban China Magazine, which is a journal devoted to analyzing the recent urbanization of China through the use of creative diagrams, graphs, articles, and photographs. It is through these creative diagrams that we are able to put together large amounts of seemingly unrelated data and see their rapidly developing cities in a different way. Even though each issue of the magazine is devoted to a particular topic they all come together to show a bigger picture of what China is experiencing. The magazine is not intended to give solutions, but to serve as an archive for future reference and dialogue between the Chinese people and their government.

It has been two years since Wang arrived in Beijing. He lives in a small quarter of a massive housing project in one of the abounding poor districts. Even though he has been working the longest, most grueling hours of his life, he remains, somehow, optimistic. Being in Beijing has allowed him to better provide for his family. As do millions like him, Wang uses his imagination to reconfigure ‘waste’ into useful objects. A broken basketball is transformed into a water bucket, umbrellas attached to electricity posts become pavilions, and wool working gloves, provided in excess by the government to their factory workers, are knit into sweaters, pants, and jackets. These are just a few examples are not isolated cases but fragments of a larger network of actions and events that constitute and characterize the ‘informal city’. It is a phenomenon distinctive of the majority of the developing countries and the ability of their residents to transform an inhospitable place into a better ‘home’.

As we approach the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century we are hungry for more intellectual forces such as Urban China Magazine to help private organizations, governments, and ourselves, understand the complexity of our ‘modern’ world. Recent changes in Chinese labor regulations that better safeguard workers’ rights is the spark for future reforms that will, we can only hope, enable Wang to return home; rural China too, will benefit from these reforms, and migration to the cities will no longer be necessary. Villages will be fully equipped with basic infrastructure, schools, hospitals, and recreational areas, which provide hope for generations to come. Urban China Magazine predicts, in their 33th issue, that we will soon see the transformation of ‘Made-in-China’ to ‘Created-in-China’, a country which will no longer be the power-horse of global industries but the hub for new cultural inventions to match ancient achievements, such as gunpowder, paper, printing, and the compass.

Text ©Carlo Aiello

Images ©New Museum / Urban China Magazine