Second Place

2015 Skyscraper Competition

Suraksha Bhatla, Sharan Sundar

India

India’s Slum population is expected to surge to 104 million (9% of the national population) by 2017*. As the nation’s disparity between the rich and poor deepens, the number of people living below poverty line (<1$ per day) has doubled over the last decade. Chennai city’s Nochikuppam slum is home to 5,000 fishermen families living in less than 1,500 shanties making it the third largest slum dwelling amongst the Indian metropolises. The rise of city’s squatters over the past decade indicated the struggle to cope with rapid urbanisation and the lack of political will, resulting in the failure of the government to regularise and successfully build resettlement tenements. The government’s only indirect response to such slums has been the construction of large-scale resettlement colonies on the outskirts of the city rather than recognising improving residents’ access to services.

Pragmatically, building adequate amounts of resettlement housing to house all slum-dwellers will simply take too long, require vast amounts of land and cost the city 1 billion rupees. Moreover, many residents do not necessarily desire such housing: reports indicate that nearly 20 % of allotted homes are vacant and 50 per cent of the original beneficiaries are no longer living in them, subletting them instead. Clearly, this was due to the fact that slum dwellers were transplanted 30 kms away from city centre where they found no jobs and no social infrastructure and thus were forced to move back to the city.

A far more reasonable strategy would be to implement the Tamil Nadu Slum Clearance Act (1971) in the spirit that it was written, and start to recognise slums and improve them in situ. The sky-high rentals in Chennai’s downtown and the fight for survival in India’s slums such as Nochikuppam are increasingly blurring the lines between centre and periphery. Urban planners face escalating challenges as these slums will mostly proliferate in semi-rural and downtown areas, a consequence of scarcity of urban land and accelerating rural to urban shift across the nation.

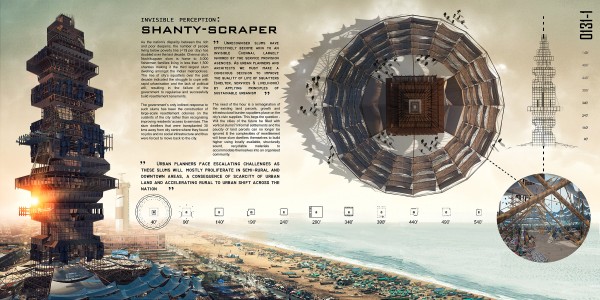

Unrecognised slums have effectively become akin to an invisible Chennai, largely ignored by the service provision agencies. As urban planners and architects we must make a conscious decision to improve the quality of life of squatters (shelter, services & livelihood) by applying principles of sustainable urbanism. The need of the hour is a reimagination of the existing land parcels, growth and infrastructural burden squatters place on the city’s civic supplies. This begs the question – Will the cities of the future be filled with vertical slums? Informal settlements and the paucity of land parcels can no longer be ignored & the complexities of resettlement will force slum dwellers themselves to build higher using locally available, structurally sound, recyclable materials accommodating themselves into organised communities.

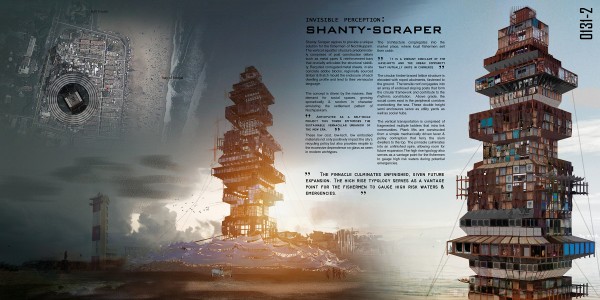

Shanty-Scraper aspires to provide a unique solution for the fishermen of Nochikuppam located at Marina bay beach. The vertical squatter structure predominately is comprised of post-construction debris such as pipes and reinforcement bars that crucially articulate the structural stability. Recycled corrugated metal sheets, regionally sourced timber & thatch mould the enclosure of each dwelling profile and lend to their vernacular language. The double height semi enclosures serve as utility yards & social gathering spaces. The vertical transportation is fragmented into multiple plank lifts that are constructed from a simple mechanically driven lever & pulley contraption. The rhythmic timber lattice membrane structure at the ground level, houses the public sea food market, & forms the first level of defence against future tsunamis. The high rise typology serves as a vantage point for the fishermen to gauge high risk waters & during emergencies.