Special Mention

2010 Skyscraper Competition

Muchan Park, Luc Wilson

United Sates

Beyond Manhattanism

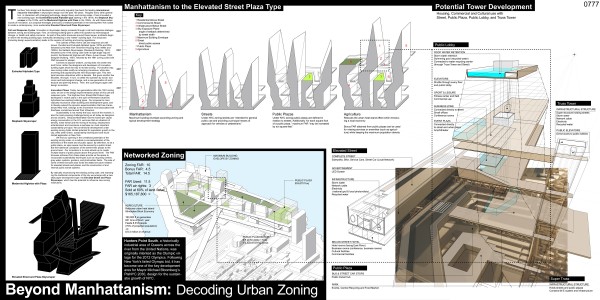

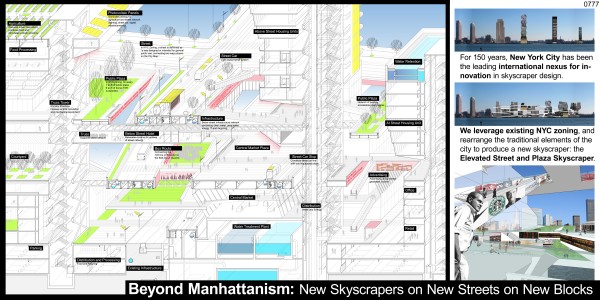

The New York design and development community arguably has been the leading international nexus for innovation in skyscraper design over the past 150 years. Roughly every other generation, in interaction with changing technology, design theory and zoning codes, it has innovated a new building type. We leverage existing NYC zoning, and rearrange the traditional elements of the city to produce a new skyscraper: the Elevated Street and Plaza Skyscraper.

Call and Response Cycles

Innovation in skyscrapper design proceeds through a call and response dialogue between zoning and building type. First, an existing building type is called into question by technological change, or health and safety concerns. As part of the public discourse around these issues, architects begin to reform the existing building type, eventually developing a new “better” building type. This discourse (including design experenentation) leads to the revision of building and zoning regulations.

The outlines of New York’s call and response are well known: Dumbell and Extruded Alphabet types (1870s and 80s), followed by the New York Tenement Housing Acts (1890s and 1900s); the Setback Skyscrapper (Woolworth Building, 1913), followed by the 1916 zoning code (with its light angle requirements); the Modernist Highrise with Plaza, (Lever House, 1952; Seagram Building, 1957), followed by the 1961 zoning code (with FAR bonuses for plazas).

Contrary to popular wisdom, zoning does not create new built forms; rather the designers and developers of innovative building types show the way to revised zoning. Put another way, new zoning codes codify an emerging concensus, while also anointing and popularizing the new skyscraper type. This new type becomes ubiquitous within a decade. But given another few decades, this type, in turn, is called into question by social, economic and technological change, and a new generation of architectural and planning theory. Then, the cycle begins again with design innovation.

Innovation Phase

Today, two generations after the 1961 zoning code, we are in the design experimentation phase of this call and response cycle, where sustainability is not merely the buzz word of the moment, it also the most pressing challenge facing us all today as designers and as citizens. Because Manhattan has the lowest per capita energy consumpation in the U.S. we know that an urbanism of density, mass transit and the mixing of housing, employment, entertainment and commerce is perhaps our most important sustainabilty principal. Yet conventional development under existing zoning holds limited potential for population growth in the city, while other sustainabilty techniques have found limited applicaiton in New York.

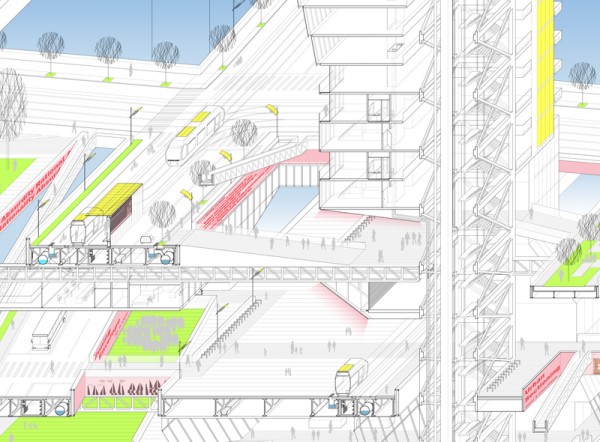

We find our opening in the unrealized potentials of the existing zoning code–in a radical reconceptualization of the definitions of the street and of public space. By definition, to be a public plaza, an open space must be served by a public street. But the traditional conception of the street limits plazas to the ground level. Our innovation is to ramp streets up to create multiple layers of public plazas above the ground level. The FAR bonuses achieved from these plaza provide us the space to incorporate sustainabilitiy techniques such as recycling centers, grey water systems, gardens, and photovoltaic fields. The sale of some of these bonuses also funds the added structure needed for elevated streets and plazas, and the construction of and internal public transit systems. Through this absurdly rational logic we emerge with a new skyscraper development type: the Elevated Street Plaza Skyscraper, which has the potential to influence new zoning resolutions.